Can one experience happiness by one’s self? Since the signifier itself is part of a linguistic structure, and language itself is a technology of a group (in this case homo sapien sapiens that speak English), I would have to answer a resounding “no!” Much like other ideological constructs, happiness is supported by the desires of a people put into language. While the signifier — like most other abstract ideas — is difficult to specifically define, we all seem to know when we are happy, or at least unhappy.

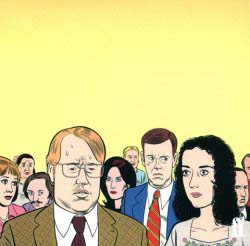

Todd Solondz’ 1998 film Happiness seems to suggest that personal happiness lies in our relationships with other people. More specifically, it seems to intimate happiness depends solely on what we can get from others. And, since others are out to fulfill their own definition of happiness, personal happiness is fleetingly rare.

Indeed, in a culture brimming with sanctioned and sactioning individualism, agreeing upon a single abstract concept like happiness becomes impossibly absurd, except in tiny amounts. Yet, the irony of the little orgasm of happiness is that those lucky enough to find it, ending up paying dearly for their discovery.

Take, for instance, the character of Joy. In her impossible quest to satisfy her individuality and her family’s and society’s expectations of her, she meets Vlad, a Russian immigrant. Vlad, in a brusque frontal assault of Russian charm, manages to seduce (and I use this term with some irony) Joy, giving her a brief moment of pleasure before being physically assaulted by Vlad’s jealous lover the next morning. Indicative of the sort of bludgeoning reality of this film, this attack implicitly suggests that any moment of happiness that we achieve always produces pain in another.

Nowhere is this lesson so explicit as in the case of Bill Maplewood, a successful psychiatrist with a taste for pedophilia. The movie depicts Maplewood’s successfully finding his happiness in the rape of two of his son’s schoolmates.

Yet, as disturbing as my somewhat bland description of this character seems to be, the most alarming aspect of the Maplewood character is our sympathy for him. In a society where pedophilia ranks up there with the egregiousness of murder, this sympathy is difficult to reconcile. Maplewood’s individual happiness is in direct conflict with the mores of his culture, making what he does monstrous. We can’t help seeing what a good father and husband Bill is, though not without his typical difficulties. Hating Maplewood becomes next to impossible for the critical viewer: Happiness shows the futility of such monolithic conceptions of morality.

Happiness is a film of striking subtly. It depicts an almost impossible road to happiness in the face of the obstacles we have created for ourselves, in social institutions and ideologies. The only happiness in the film seems to lie in the elusive orgasm, something Maplewood’s young son Billy chases throughout the film, only to succeed during the last scene. He is finally able to announce to his collective family: “I came.”

Is contemporary society so ossified that the only happiness we have is in the product of masturbation? Goodness, I hope not, but this film is worth a look, especially for the opening scene. As much of a downer as Happiness turns out to be, there are genuinely funny moments, but like the orgasm, they last only momentarily.